An astounding 97% of websites don’t offer a fully accessible digital experience to their users. This is despite the fact that millions in the UK self-identify as having a disability or an impairment that impacts their ability to use technology. Additionally, the 2019 Click-Away Pound survey found that 70% of people will leave a website if it doesn’t meet their accessibility needs.

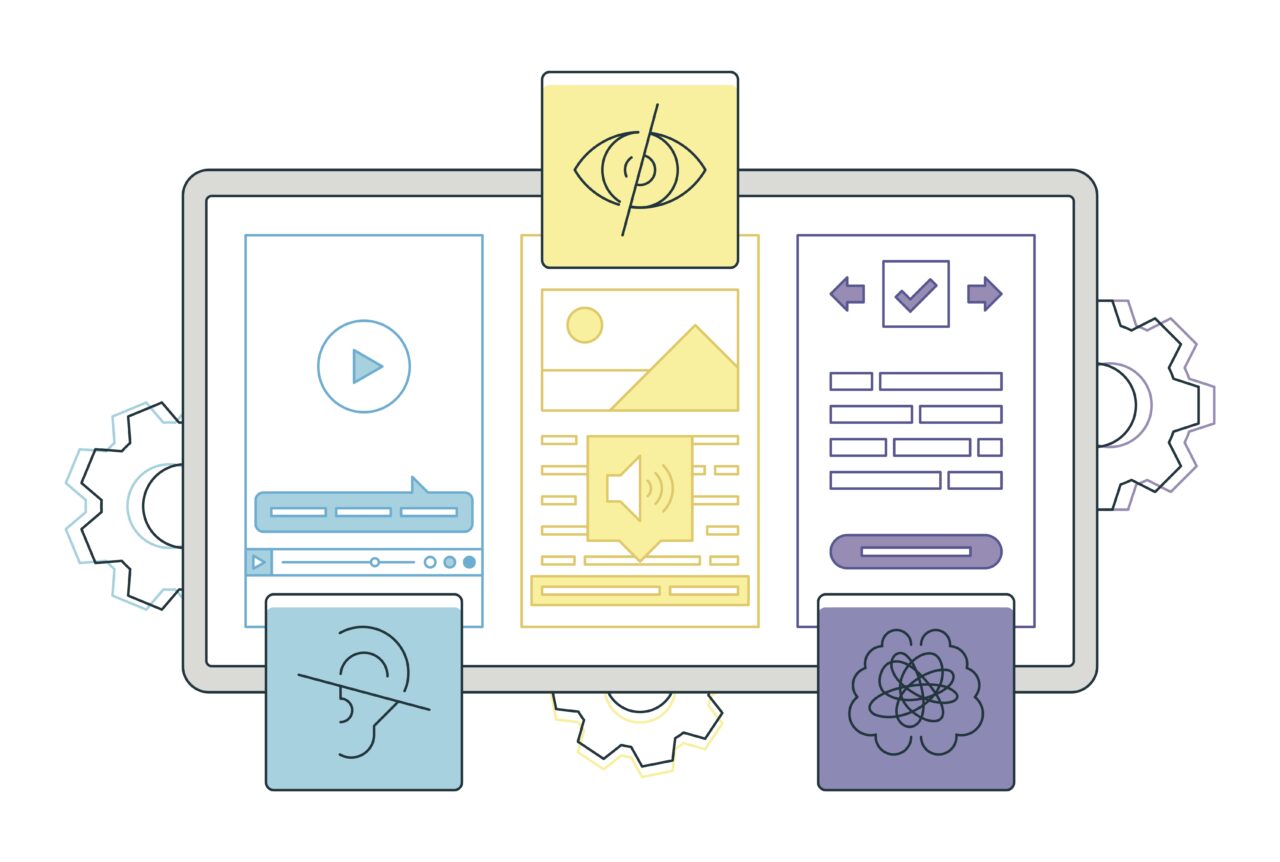

To help increase the accessibility of the internet, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) created four principles to ensure a fully accessible digital experience for customers. These are about to be refreshed with an updated set of guidelines – WCAG 2.2 – which will aim to keep pace with the changing nature of the internet as the average age of web-users continues to increase.

Gov.uk has further simplified the guidelines with a series of questions that goes through each of the four principles; answering “yes” to all of them means your website is well on its way to ensuring an inclusive digital experience.

In not doing so, organisations could be missing out on valuable revenue – not to mention failing to meet laws and regulations around accessibility.

Myths and laws of accessibility

There’s a common misconception that accessibility is inherently difficult to implement in websites. But it isn’t – particularly when the design team and developers work together in the earlier stages of the project. Here are some of the most frequent myths around the topic:

- The ordering of content and elements on a website is vital to take into consideration. This means that content should naturally flow from top to bottom in a meaningful sense, so as not to confuse or disorientate users. Examples include ensuring that HTML headings are implemented in the right order, and that users are not jumping from one topic of information to the next in an abrupt manner.

- Having an accessible website doesn’t mean you can’t have rich media content like videos, animations, or gifs. It is possible to include these. However, in doing so, it is essential that all accessibility considerations are implemented to make these pieces of content usable and inclusive. This might be that all videos on a webpage have accessible controls to play, pause, mute, fast forward and rewind the video. Screen reader technologies must also clearly describe the actions of each control.

- Another myth is that building websites to an accessible standard is time consuming and costly. If accessibility is considered during the early stages of site development, then the implementation will only need to happen once rather than be revisited. When accessibility isn’t factored in from the start and/or is neglected ongoing during content management, it can cause issues further down the line.

UK law only requires that their website is accessible in compliance with The Public Sector Bodies regulations. However, the private sector has a duty, under the Equality Rights Act 2010, for an accessible site. Although not yet enforced by the courts, anyone who feels they’ve been discriminated against by a UK organisation due to inaccessibility has the right to bring a claim.

Indeed, there have been cases where private organisations faced a lawsuit, but instead changed their website and settled out of court to avoid legal action such as RNIB v BMI-baby.

Overcoming failures when building a fully accessible digital experience

So, what are some common ways many content creators fail in providing accessibility?

- Links: any link on a website should contain an aria label (a description of the links purpose and what action it will perform when activated). If not considered, links can be open to user interpretation which can be greatly misleading, and leave users lost as to where to go next. Additionally, sometimes insensitive words are used for visually impaired users. Terms such as ‘click here to see more’ might not be optimum. Instead, consider the use of terms like ‘follow this link to learn more’ which conveys the same meaning in a less harmful manner.

- Colour contrast: all content teams and editors need to stay mindful that any imagery used must consider the colour of text that overlays it. For example, in an image where there are many colours, can you ensure that the colour contrast remains in an acceptable accessible range? Or does it fall out with this guideline? The use of a masked background colour behind the text which is slightly opaque can resolve the issue.

- VFI’s (Visual Focus Indicators): outlines that highlights when a user focuses on actionable elements on a website are sometimes not implemented in an accessible way, if at all. If deployed correctly, these should let a user use the Tab or Arrow keys to navigate through the site. When VFI’s don’t have a suitable colour contrast, the user can become lost when attempting to explore the site. Ensuring a clear contrast ratio greatly helps aid in the visual clarity of a user’s position on a page.

- Text based images: items such as charts can be overlooked, as visually impaired users cannot ingest this information. To ensure this is not the case, consider using HTML tables or other means to present the information, rather than a graphical sense. If it is that a graphic must be used, an ALT tag (alternative) can be used. This is used to describe and convey the image and its inner contents to screen readers and other tools.

More than one billion people around the world experience accessibility issues every day. Even for those of us who don’t, we must aim to meet all customers’ needs, regardless of ability. It’s not just a legal and moral duty; it makes good business sense.