This article by Nicolle Paradise was written in conjunction with Dr Kristin Walle, Division Vice President of Global Money Movement & Compliance/Shared Services Compliance Solutions at ADP.

Too sensitive? Just suck it up, buttercup. Too abrasive? Bull in a china shop.

And somewhere in-between these extremes, there’s us: you and me. We’re leaders, we’re employees, and we understand that at the most basic level, those who don’t know what is expected of them seldom perform to their potential.

Astonishingly, Gallup research suggests that nearly 70 percent of all US employees aren’t working to their full potential in a given business day.

To communicate what’s expected, is it as binary as: “If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all” versus “You Can’t Handle The Truth!” (thanks, Jack Nicholson)? No, we disagree with this positioning and what lies in-between is what we will explore.

We believe leaders have a fundamental responsibility to create value through direct communication. This communication style benefits the Employee Experience and is good for business. Direct communication, defined as the ability to consume, interpret, and mirror back, leaves very little room for interpretation of the employee’s value, their value to the business, and value to customers. This process also subtly communicates the message of “you care about me”, from leader to employee.

With so much to gain then, why do leaders resist direct communication? According to a 2016 study published in Harvard Business Review, “69 percent of managers reported being uncomfortable communicating in general with employees”. If two out of three of leaders are uncomfortable with general communication, we begin to understand just how uncomfortable most leaders would be with direct communication.

To help bridge this communication gap between what makes most of us uncomfortable with what employees need to achieve their full potential, let’s examine a case study between Jack (SVP, Customer Success) and Oliver (VP, Customer Success), a direct report of Jack’s.

Jack was frustrated with the number of escalations he was receiving from Oliver. He believed he had clearly addressed Oliver’s concerns around how to manage escalations and when that volume did not decrease, but instead the escalations increased, it caused several related outputs:

- From a leadership perspective, Jack believed that Oliver was choosing to not follow the appropriate direction.

- Through that lens, Jack interpreted the escalations from employees who were bypassing Oliver as being directly caused by Oliver’s choice to not follow directions.

- Customers expressed concern at the increased amount of time it was taking to address their issues.

Observing the impact to both employees and customers, Jack decided to confront Oliver as to why he chose to ignore the provided guidance.

Oliver, however, was confused and himself, frustrated. He was a proven, competent VP within the organisation and asked his manager, Jack: “What specifically are you asking me to do differently? I thought I was following your exact direction this entire time.”

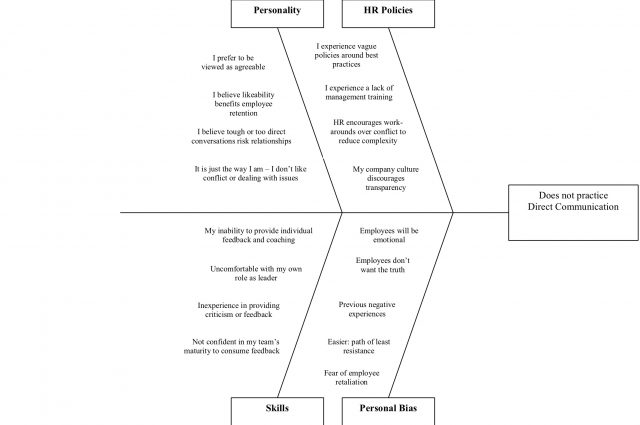

Why did this stark miscommunication happen? To answer that, we leveraged an Ishikawa diagram to uncover the potential cause and effect.

We first identified what specific areas, either internal (e.g: ‘personality’) or external (‘HR policies’) may be perceived obstacles. Then within each category we identified several potential reasons ( e.g: ‘I prefer…’) why this prevented the desired outcomes.

This diagram helped Jack get to the root cause of the disconnect. Jack, unintentionally, had concluded the root cause of the escalations solely through his own perceptions, not via direct communication with Oliver. By broadening his perspective and asking direct questions of Oliver, Jack was then able to provide clear, consumable feedback related to Oliver’s performance, goals, and associated metrics. This renewed clarity of communication benefited Oliver, Oliver’s team, and ultimately, the 10,000 customers that the organisation supports.

This diagram also helped Oliver contemplate his own obstacles. He realised that his assumptions prevented him from asking specific, clarifying questions to Jack. Understanding that Jack may not be skilled or may have his own bias around the interaction, Oliver learned to probe and paraphrase back to Jack in a manner so that clarity was achieved.

Several iterations of the diagram are commonly needed to yield the desired clarity, so patience from both leaders and employees is needed until the skills have been developed.

Additionally, we recommend the organisation ask itself a few proactive questions with a focus toward driving direct communication:

- How are we ensuring that the root cause issue is actually the root cause?

- What is the result we are looking for as an organisation? Why it this important and how is it measured?

- How does this connect to the overall organisational benefits?

This feedback loop – comprised of the above proactive questions and the Ishikawa diagram analysis – position organisations to communicate directly regarding behaviours that contribute to achieving specific goals as well as identify which behaviours contribute to creating obstacles. From a communication perspective, this feedback loop helps balance the extremes of “too sensitive: suck it up, buttercup” and “too abrasive: bull in a china shop”.

Today’s leaders are investing in the leaders of tomorrow, ultimately yielding a richer and more developed employee, an improved experience, and thus higher employee retention rates. The stability that this feedback loop provides an organisation has a direct, positive impact on development, collaboration and creativity, delivering value for both employees and customers.

When we know what is expected of us, we can perform to our full potential. How might leveraging this feedback loop help your team reach their full potential?